A Tale of Tutor Texts

Have you ever had one of those books that let you choose your own adventure? You know, the book will say “The bully tells you to hand over the secret message. If you want to run away, turn to page 48. If you want to fight him, turn to page 70.” While this is normally a staple of children’s literature, there were a series of training books known as Tutor Texts that used the format to teach technical topics.

In fact, one of these books was my first introduction to computer programming more years ago than I care to admit. But it wasn’t just computer programming. There were titles from the same publisher about trigonometry, slide rules, and even how to play bridge. I own four of these old books and it got me to thinking about how we deliver information on the web. Maybe these books were ahead of their time.

The Advantage

Assuming a book like this is well constructed, this is a pretty good idea. A regular book just tells you something and then — maybe — asks you a question or two to see if you got the idea right. If you don’t, you have to go back and reread the same material that didn’t make sense to you in the first place.

Assuming a book like this is well constructed, this is a pretty good idea. A regular book just tells you something and then — maybe — asks you a question or two to see if you got the idea right. If you don’t, you have to go back and reread the same material that didn’t make sense to you in the first place.

If you think back to some skill you struggled with, you can probably see the value of getting a second or even third take on the same topic. For example, think about learning to tie your shoes or even a necktie. It probably seems effortless now, but whoever taught you probably had to show you several different ways. Ditto for riding a bike.

With the Tutor Text approach — technically known as programmed instruction — this isn’t how it works. You are given a problem and if you choose the wrong answer, you are directed to a new different explanation. Once in awhile the text will simply give you an explanation and tell you to go back and try again, but often the wrong answer pages take you on a detour path to correct your thinking before rejoining the main line of the book.

As a side note, there are other techniques that also fall under the umbrella of programmed instruction, training, or learning. For the purpose of this post, I mean programmed instruction to be in the style of the Tutor Texts: ask a multiple choice question and then explain why it was correct or incorrect before proceeding. As far as I can tell, the technique originated with the US Air Force where psychologist Norman Crowder used it to efficiently train maintenance crews in the 1960s.

For Example

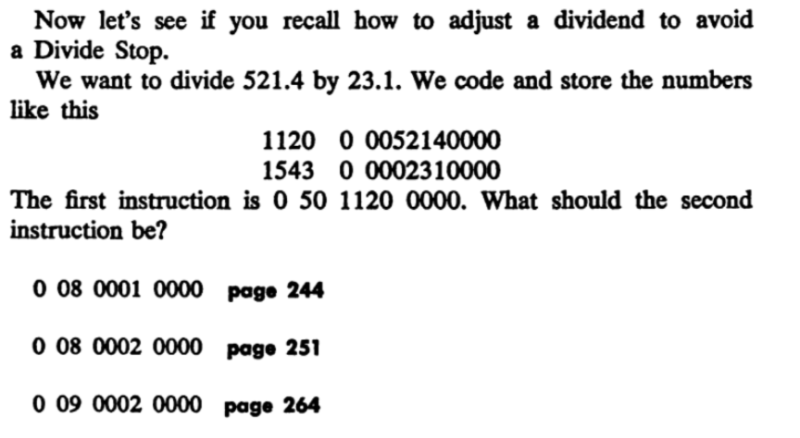

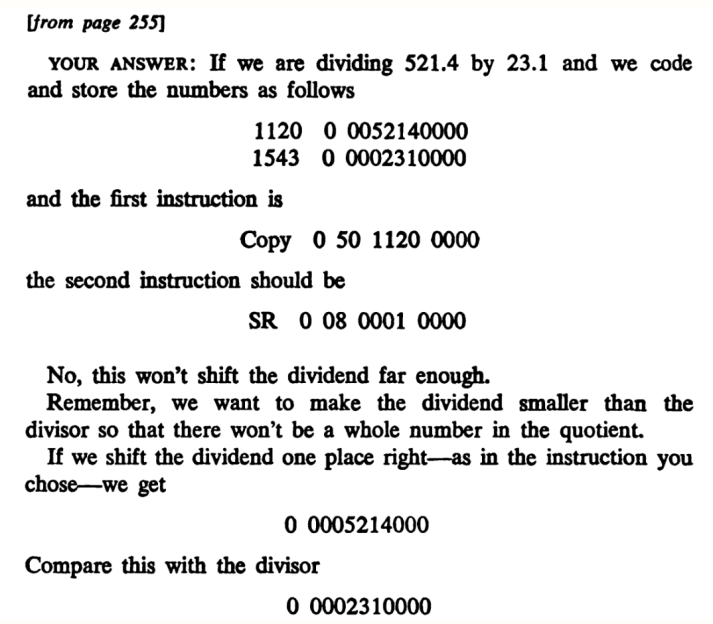

For example, in the computer programming version of the book, they are using an imaginary machine called TUTAC that works with decimal numbers — not unheard of in the 1960s. (We’ve talked about the TUTAC and other made up machines of those days before.)

Here’s an example problem:

Honestly, I don’t remember the answer — I haven’t really read this book since I was 12 years old. But let’s just randomly pick the first answer and go to page 244:

Oops. From the context of this answer, I’m guessing the correct answer was on page 251. That page not only reports you are correct but explains why you are correct before posing a new question. Sometimes there is new information before the new question and sometimes it is just a multi-part question.

The Problem

Although the better topics lead you to more practice problems when you stumble, the more complex ones tend to give you an explanation and then send you back to the question to try again. Why? If you try writing something like this yourself, you find that it quickly spirals out of control. You explain A but the reader doesn’t get get it. So you explain it again, but still no dice. So you review something from the past and ask again. Nothing. Now what? There has to be some limit to how much you branch.

Sometimes it is hard to know in advance the topics people aren’t going to understand. If you’ve ever tried to teach someone to tie a tie or ride a bike, you know what I mean. It is so easy once you know how. But until you get to that point it is nearly impossible and — worse — once you do know, you forget why it was so hard in the beginning. Ideally, you want to design questions that have answers that indicate where there is a misunderstanding.

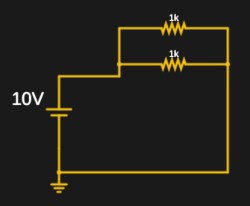

For example, if I showed a picture of two resistors in parallel connected to a 10 V battery, I might ask: What’s the voltage across the two resistors? The correct answer, of course, is 10 V. But I might throw in 5 V as a decoy answer because some people might think the resistors split the voltage, for example. Another answer might be 10 divided by the sum of the resistors in case someone thought it was an Ohm’s law problem.

For example, if I showed a picture of two resistors in parallel connected to a 10 V battery, I might ask: What’s the voltage across the two resistors? The correct answer, of course, is 10 V. But I might throw in 5 V as a decoy answer because some people might think the resistors split the voltage, for example. Another answer might be 10 divided by the sum of the resistors in case someone thought it was an Ohm’s law problem.

There’s also the problem of combinatorial explosion. Let’s say you have a topic about interpreting a data dump and from the answer the reader chooses, you realize they don’t know hexadecimal. No problem, you just write a topic on that. But now you realize they don’t understand exponents. Chains like this can go on and on.

Modern Day

You do see programmed instruction from time to time in your Web browser, but you’d think it would be ubiquitous, and it isn’t. A lot of training courses are little more than overhead slides converted to PowerPoint. Yet this seems like a missed opportunity.

Think about it. With a computer-based text, you would have a lot more options. The excellent EDx electrical engineering class, for example, can give you random practice questions. I assume the author could give a range of values and relationships (e.g., R1=5K to 10K, R2=(1.8 to 2.2)*R1). The computer solves the problem and knows the answer. So if you work the same practice problem four or five times, you get a different answer each time.

Imagine a report that showed which incorrect answers have the most hits and, perhaps, which have none. Which topics have a high percentage of incorrect responses the first time through? Maybe that text needs some additional thought. How long do students read a topic before answering? Lots of data to mine that could make the material better.

It is interesting that if you search Google for “programmed instruction” most of what you get back are pedagogical articles about the technique. There are a few other books that have used the technique. However, more used a different form proposed by B. F. Skinner where questions and answers appear after a short bit of text. “Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess” is a good example, as is Quick Calculus.

It is interesting that if you search Google for “programmed instruction” most of what you get back are pedagogical articles about the technique. There are a few other books that have used the technique. However, more used a different form proposed by B. F. Skinner where questions and answers appear after a short bit of text. “Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess” is a good example, as is Quick Calculus.

Radio Shack had a ham radio course called “From 5 Watts to 1,000 Watts” that proudly proclaimed it was a programmed course. While a lot of online courses do insert activities as these books do, there are few that do the multiple-choice/explanation style that the Tutor Text uses.

Future

Maybe one day this kind of programmed instruction will be popular again. It wouldn’t be hard to build a web-based framework to present this kind of thing. You could even do it with PowerPoint, in a crude way. After all, in the 1960s they did it with paper.

Meanwhile, the Tutor Text stands as a great tribute to the concept. They taught me a lot, and I’m sure a lot of others, too. Of course, nowadays you can also take college courses online, many for free. Or go old school and learn electronics from the Navy.

from Hackaday https://ift.tt/31CrHpN

Comments

Post a Comment