DSL is Barely Hanging on the Line as Telcos Stop Selling New Service

Are you reading this over AT&T DSL right now? If so, you might have to upgrade or go shopping for a new ISP soon. AT&T quietly stopped selling new traditional DSLs on October 1st, though they will continue to sell their upgraded fiber-to-the-node version. This leaves a gigantic digital divide, as only 28% of AT&T’s 21-state territory has been built out with full fiber to the home, and the company says they have done almost all of the fiber expansion that they intend to do. AT&T’s upgraded DSL offering is a fiber and copper hybrid, where fiber ends at the network node closest to the subscriber’s home, and the local loop is still over copper or coax.

At about the same time, a report came out written jointly by members of the Communications Workers of America union and a digital inclusion advocacy group. The report alleges that AT&T targets wealthy and non-rural areas for full fiber upgrades, leaving the rest of the country in the dark.

As the internet has been the glue holding these unprecedented times together, this news comes as a slap in the face to many rural customers who are trying to work, attend school, and see doctors over various videoconferencing services.

As the internet has been the glue holding these unprecedented times together, this news comes as a slap in the face to many rural customers who are trying to work, attend school, and see doctors over various videoconferencing services.

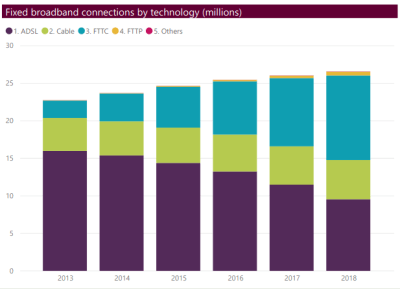

If you live in a big enough city, chances are you haven’t thought of DSL for about twenty years, if ever. It may surprise you to learn of the popularity of ADSL in the United Kindom. ADSL the main source of broadband in the UK until 2017, having been offset by the rise of fibre-to-the-cabinet (FTTC) connections. However, this Ofcom report shows that in 2018 ADSL still made up more than a third of all UK broadband connections.

Why do people still have it, and what are they supposed to do in the States when it dries up?

What is DSL, Anyway?

DSL stands for Digital Subscriber Line, and it’s essentially internet over copper. Up until the mid-1990s, many people accessed the internet by using modems of various baud rates, myself included. To use the modem, one had to tie up the phone line for the duration.

When DSL came out, it was not only faster than the fastest modem you could get at the big box store, you could use the DSL and talk on the phone at the same time. I personally never had a DSL. They were expensive, and by the time I was paying for my own internet, cable modems were gaining favor in the United States. They cost about as much per month, but were touted as being faster than DSLs. I wanted cable TV anyway, so it made sense.

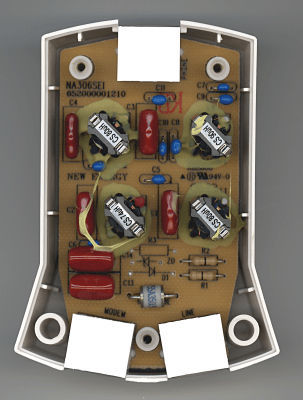

DSL works by using frequencies above the voice frequencies, so it can coexist on the copper with the voice line. In order to keep DSL frequencies from bleeding over and echoing into voice calls, there are analog low-pass DSL filters, splitters, and combination filter-splitters that separate the lines. Before they reach the wider Internet, DSLs are aggregated at the central office into a Digital Subscriber Line Access Multiplexer, or DSLAM, and then fed into the switch.

DSL flavors

When people speak of modern DSLs, they are usually talking about Asynchronous DSL, or ADSL. The download speeds range from about 5-35 Mbps and uploads average 1-10 Mbps. The asymmetry is in the data throughput: upload speeds are slower than download speeds, because people usually do more downloading than uploading.

In Synchronous DSL (SDSL), the throughput is symmetrical. There is also VDSL and VDSL2 — two tiers of Very high-speed DSL. VDSL speeds can reach 52Mbps downstream and 16Mbps upstream, and VDSL2 maxes out around 100Mbps both ways.

DSL also comes as “wet” or “dry”. If you have a wet DSL, the copper pairs also carry voice. A dry DSL has DSL only. This nomenclature comes from early voice circuitry, which needed batteries to detect whenever you picked up the phone to dial. Dry loop lines weren’t connected to batteries, and got all the power they needed from the central office.

Leaving People in the Dark

The report by CWA and NDIA also accuses AT&T of “digital red-lining” in urban centers, which essentially favors the rich in cities like Cleveland and Detroit where fiber build-outs are concerned. AT&T naturally denies any so-called red-lining activity.

Some urban customers are lucky enough to have other options, like cable, fiber, or satellite access. But many people in rural areas don’t have the luxury of shopping around. Where AT&T is leaving or has already left, subscribers are forced to buy from the incumbent cable company or whatever else is available. They don’t have the luxury of shopping around for the best deal or even the fastest connection.

Dark Copper

AT&T aren’t the only ones abandoning DSL. Verizon is killing it off everywhere they have fiber service, and no new customers can buy DSL in FiOS territory. Plenty of people still rely on plain old DSL, and this is a terrible time to leave those customers in the lurch. It’s also a shame that so much copper is being left to rot in the elements when it could be taken over by municipalities that could use the lines to ensure that every home that still has copper can have some kind of internet access.

So, Hackaday, are we reaching you on old-fashioned AT&T DSL? What are your plans? If you have DSL and aren’t affected by this, what do you think of it? If nothing else, DSL is robust: it will even run over wet string.

from Hackaday https://ift.tt/37RAmIn

Comments

Post a Comment